The specter of constant surveillance hangs over all of us in ways we don’t even fully understand, but it is also possible to turn the tools of the watchers against them. Forensic Architecture is exhibiting several long-term projects at the Museum of Art and Design in Miami that use the omnipresence of technology as a way to expose crimes and violence by oppressive states.

Over seven years Eyal Weizman and his team have performed dozens of investigations into instances of state-sponsored violence, from drone strikes to police brutality. Often these events are minimized at all levels by the state actors involved, denied or no-commented until the media cycle moves on. But sometimes technology provides ways to prove a crime was committed and occasionally even cause the perpetrator to admit it — hoisted by their own electronic petard.

Sometimes this is actual state-deployed kit, like body cameras or public records, but it also uses private information co-opted by state authorities to track individuals, like digital metadata from messages and location services.

For instance, when Chicago police shot and killed Harith Augustus in 2018, the department released some footage of the incident, saying that it “speaks for itself.” But Forensic Architecture’s close inspection of the body cam footage and cross reference with other materials makes it obvious that the police violated numerous rules (including in the operation of the body cams) in their interaction with him, escalating the situation and ultimately killing a man who by all indications — except the official account — was attempting to comply. It also helped additional footage see the light which was either mistakenly or deliberately left out of a FOIA release.

In another situation, a trio of Turkish migrants seeking asylum in Greece were shown, by analysis of their WhatsApp messages, images and location and time stamps, to have entered Greece and been detained by Greek authorities before being “pushed back” by unidentified masked escorts, having been afforded no legal recourse to asylum processes or the like. This is one example of several recently that appear to be private actors working in concert with the state to deprive people of their rights.

Situated testimony for survivors

I spoke with Weizman before the opening of this exhibition in Miami, where some of the latest investigations are being shown off. (Shortly after our interview he would be denied entry to the U.S. to attend the opening, with a border agent explaining that this denial was algorithmically determined; we’ll come back to this.)

The original motive for creating Forensic Architecture, he explained, was to elicit testimony from those who had experienced state violence.

“We started using this technique when in 2013 we met a drone survivor, a German woman who had survived a drone strike in Pakistan that killed several relatives of hers,” Weizman explained. “She has wanted to deliver testimony in a trial regarding the drone strike, but like many survivors her memory was affected by the trauma she has experienced. The memory of the event was scattered, it had lacunae and repetitions, as you often have with trauma. And her condition is like many who have to speak out in human rights work: The closer you get to the core of the testimony, the description of the event itself, the more it escapes you.”

The approach they took to help this woman, and later many others, jog her own memory, was something called “situated testimony.” Essentially it amounts to exposing the person to media from the experience, allowing them to “situate” themselves in that moment. This is not without its own risks.

“Of course you must have the appropriate trauma professionals present,” Weizman said. “We only bring people who are willing to participate and perform the experience of being again at the scene as it happened. Sometimes details that would not occur to someone to be important come out.”

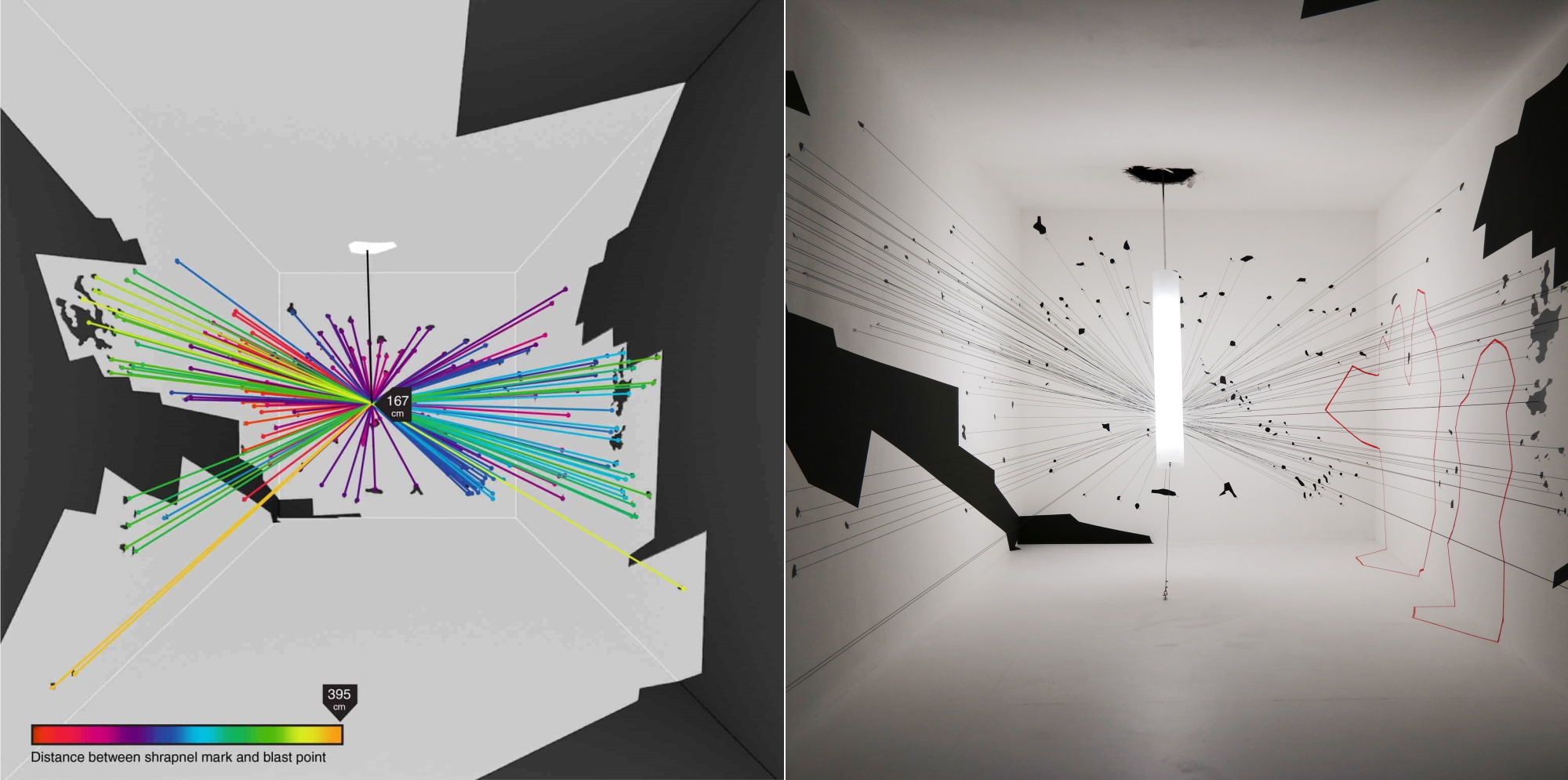

A digital reconstruction of a drone strike’s explosion was recreated physically for another exhibition.

But it’s surprising how effective it can be, he explained. One case exposed American involvement hitherto undisclosed.

“We were researching a Cameroon special forces detention center, torture and death in custody occurred, for Amnesty International,” he explained. “We asked detainees to describe to us simply what was outside the window. How many trees, or what else they could see.” Such testimony could help place their exact location and orientation in the building and lead to more evidence, such as cameras across the street facing that room.

“And sitting in a room based on a satellite image of the area, one told us: ‘yes, there were two trees, and one was over by the fence where the American soldiers were jogging.’ We said, ‘wait, what, can you repeat that?’ They had been interviewed many times and never mentioned American soldiers,” Weizman recalled. “When we heard there were American personnel, we found Facebook posts from service personnel who were there, and were able to force the transfer of prisoners there to another prison.”

Weizman noted that the organization only goes where help is requested, and does not pursue what might be called private injustices, as opposed to public.

“We require an invitation, to be invited into this by communities that invite state violence. We’re not a forensic agency, we’re a counter-forensic agency. We only investigate crimes by state authorities.”

Using virtual reality: “Unparalleled. It’s almost tactile.”

In the latest of these investigations, being exhibited for the first time at MOAD, the team used virtual reality for the first time in their situated testimony work. While VR has proven to be somewhat less compelling than most would like on the entertainment front, it turns out to work quite well in this context.

“We worked with an Israeli whistleblower soldier regarding testimony of violence he committed against Palestinians,” Weizman said. “It has been denied by the Israeli prime minister and others, but we have been able to find Palestinian witnesses to that case, and put them in VR so we could cross reference them. We had victim and perpetrator testifying to the same crime in the same space, and their testimonies can be overlaid on each other.”

Dean Issacharoff — the soldier accused by Israel of giving false testimony — describes the moment he illegally beat a Palestinian civilian. (Caption and image courtesy of Forensic Architecture)

One thing about VR is that the sense of space is very real; if the environment is built accurately, things like sight-lines and positional audio can be extremely true to life. If someone says they saw the event occur here, but the state says it was here, and a camera this far away saw it at this angle… these incomplete accounts can be added together to form something more factual, and assembled into a virtual environment.

“That project is the first use of VR interviews we have done — it’s still in a very experimental stage. But it didn’t involve fatalities, so the level of trauma was a bit more controlled,” Weizman explained. “We have learned that the level and precision we can arrive at in reconstructing an incident is unparalleled. It’s almost tactile; you can walk through the space, you can see every object: guns, cars, civilians. And you can populate it until the witness is satisfied that this is what they experienced. I think this is a first, definitely in forensic terms, as far as uses of VR.”

A photogrammetry-based reconstruction of the area of Hebron where the incident took place.

In video of the situated testimony, you can see witnesses describing locations more exactly than they likely or even possibly could have without the virtual reconstruction. “I stood with the men at exactly that point,” says one, gesturing toward an object he recognized, then pointing upwards: “There were soldiers on the roof of this building, where the writing is.”

Of course it is not the digital recreation itself that forces the hand of those involved, but the incontrovertible facts it exposes. No one would ever have known that the U.S. had a presence at that detainment facility, and the country had no reason to say it did. The testimony wouldn’t even have been enough, except that it put the investigators onto a line of inquiry that produced data. And in the case of the Israeli whistleblower, the situated testimony defies official accounts that the organization he represented had lied about the incident.

Avoiding “product placement” and tech incursion

Sophie Landres, MOAD’s curator of Public Programs and Education, was eager to add that the museum is not hosting this exhibit as a way to highlight how wonderful technology is. It’s important to put the technology and its uses in context rather than try to dazzle people with its capabilities. You may find yourself playing into someone else’s agenda that way.

“For museum audiences, this might be one of their first encounters with VR deployed in this way. The companies that manufacture these technologies know that people will have their first experiences with this tech in a cultural or entertainment contrast, and they’re looking for us to put a friendly face on these technologies that have been created to enable war and surveillance capitalism,” she told me. “But we’re not interested in having our museum be a showcase for product placement without having a serious conversation about it. It’s a place where artists embrace new technologies, but also where they can turn it towards existing power structures.”

Boots on backs mean this not an advertisement for VR headsets or 3D modeling tools.

She cited a tongue-in-cheek definition of “mixed reality” referring to both digital crossover into the real world and the deliberate obfuscation of the truth at a greater scale.

“On the one hand you have mixing the digital world and the real, and on the other you have the mixed reality of the media environment, where there’s no agreement on reality and all these misinformation campaigns. What’s important about Forensic Architecture is they’re not just presenting evidence of the facts, but also the process used to arrive at these truth claims, and that’s extremely important.”

In openly presenting the means as well as the ends, Weizman and his team avoid succumbing to what he calls the “dark epistemology” of the present post-truth era.

“The arbitrary logic of the border”

As mentioned earlier, Weizman was denied entry to the U.S. for reasons unknown, but possibly related to the network of politically active people with whom he has associated for the sake of his work. Disturbingly, his wife and children were also stopped while entering the states a day before him and separated at the airport for questioning.

In a statement issued publicly afterwards, Weizman dissected the event.

In my interview the officer informed me that my authorization to travel had been revoked because the “algorithm” had identified a security threat. He said he did not know what had triggered the algorithm but suggested that it could be something I was involved in, people I am or was in contact with, places to which I had traveled… I was asked to supply the Embassy with additional information, including fifteen years of travel history, in particular where I had gone and who had paid for it. The officer said that Homeland Security’s investigators could assess my case more promptly if I supplied the names of anyone in my network whom I believed might have triggered the algorithm. I declined to provide this information.

This much we know: we are being electronically monitored for a set of connections – the network of associations, people, places, calls, and transactions – that make up our lives. Such network analysis poses many problems, some of which are well known. Working in human rights means being in contact with vulnerable communities, activists and experts, and being entrusted with sensitive information. These networks are the lifeline of any investigative work. I am alarmed that relations among our colleagues, stakeholders, and staff are being targeted by the US government as security threats.

This incident exemplifies – albeit in a far less intense manner and at a much less drastic scale – critical aspects of the “arbitrary logic of the border” that our exhibition seeks to expose. The racialized violations of the rights of migrants at the US southern border are of course much more serious and brutal than the procedural difficulties a UK national may experience, and these migrants have very limited avenues for accountability when contesting the violence of the US border.

The works being exhibited, he said, “seek to demonstrate that we can invert the forensic gaze and turn it against the actors — police, militaries, secret services, border agencies — that usually seek to monopolize information. But in employing the counter-forensic gaze one is also exposed to higher-level monitoring by the very state agencies investigated.”

Forensic Architecture’s investigations are ongoing; you can keep up with them at the organization’s website. And if you’re in Miami, drop by MOAD to see some of the work firsthand.

Recent Comments